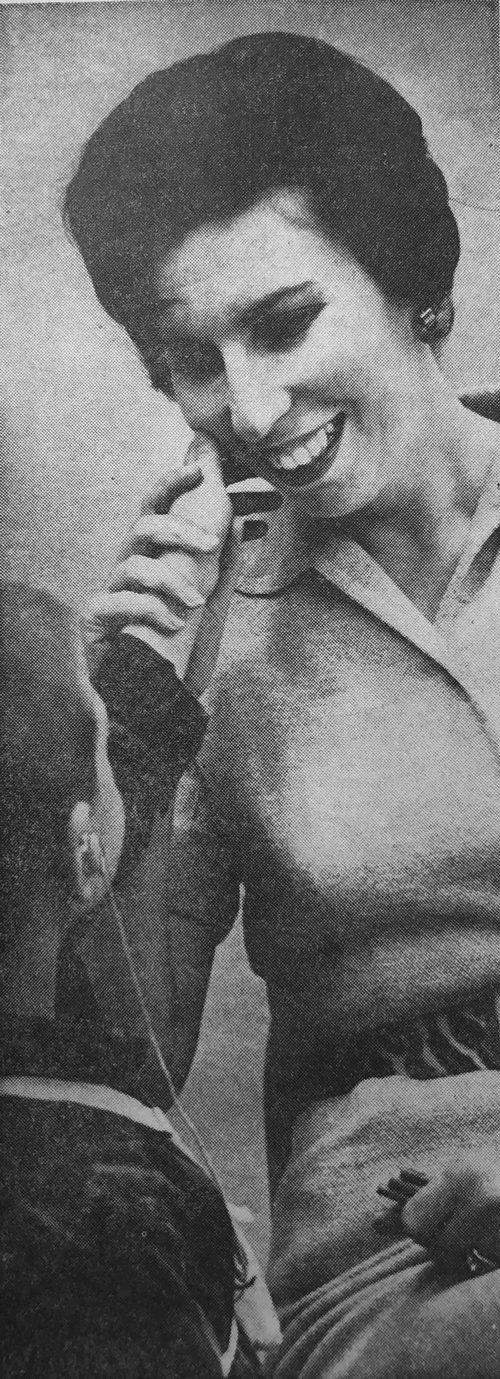

Bernie Leo Leff (1965)

Disclaimer: The following was transcribed from an article in the Capper Foundation Archives published by the Topeka State Journal. The choice of words used at the time this was written may not reflect current Capper Foundation inclusive language and views.

She Teaches Deaf Children to Speak (1965)

“Any deaf child with normal intelligence can learn to speak and lip read,” Mrs. Bernie Leo Leff insisted. This is the philosophy that Mrs. Leff has been using in teaching six deaf and hard of hearing children to speak correctly at the Capper Foundation since September. Mrs. Leff teaches at Capper from 9 a.m. until 11:30 a.m. every day. In addition to a class of four boys, 4 and 5 years old and all deaf, she is teaching two hard of hearing girls, 5 and 7, separately. She also teaches children privately in her home.

A native of St. Louis, she first became interested in teaching deaf children during her junior year in high school when a teacher from the Central Institute for the Deaf, a part of Washington University in St. Louis, came to her school to conduct a demonstration of her class at the institute. After a visit to the institute, Mrs. Leff knew what she wanted to do and after she graduated from the Teacher Training Division of the institute, she worked there for some time.

“I’d always been interested in language, its formation and usage, and in little children, and these go together in teaching deaf children,” Mrs. Leff shared. She then went to Houston, Tex., where she taught deaf children in the public schools. She met her husband there and the family lived there until three years ago when her husband was transferred to Topeka.

Until September, she taught children privately in her home, but last fall three circumstances coincided, giving her a chance to return to the classroom.

First, the Capper Foundation suddenly and for the first time had several deaf children all at once. Second, the state special education department decided that something should be done locally about teaching the deaf. Finally, Gordon began nursery school in the mornings, freeing her for classes at that time.

The classes, beginning on an experimental basis, will continue for another year. At the time, the boys will be old enough to enter a special school for the deaf, such as the one in Olathe. “The Capper Foundation,” Mrs. Leff explained, “is a nonprofit organization that teaches the physically handicapped child a restricted program of study because of their handicap that the public schools can’t provide them.”

The classes, beginning on an experimental basis, will continue for another year. At the time, the boys will be old enough to enter a special school for the deaf, such as the one in Olathe. “The Capper Foundation,” Mrs. Leff explained, “is a nonprofit organization that teaches the physically handicapped child a restricted program of study because of their handicap that the public schools can’t provide them.”

Her students are taught speech, lip reading and language development. All of it is taught orally and she doesn’t use any finger spelling or sign language. Her biggest problem, she admits, is to forget the children are deaf when she walks into the room so she can talk to them just as one would speak to a child with normal hearing. After the children are able to lip read one or two of the words she speaks, they usually can tell, from experience or from the present situation, what she is saying. Most of the children come to her with little or no language at all, though they can recognize a few words, usually things such as their names, which they have seen said often.

The first thing Mrs. Leff does is attempt to get a sound from the child. She does this by having the children feel her throat as she pronounces the sound over and over again. Then each child tries to reproduce the same sound as the teacher.

“Each phonetic sound has its own formation and I have to teach all these and then form them into words,” she said. Every sound a person makes has to be taught to a deaf child, since they can’t pick up things that a child with normal hearing can.

“You have to be the type of person who doesn’t demand quick returns on the time you spend,” she commented, since the process of making them speak well in sentences takes about two years. The first word is usually heard in about a week, although some won’t say it for as long as six months. On an average, it is about six months before a deaf child can repeat a sentence, one to two years before they can relate things spontaneously, and four or five years before they can really be said to be conversing.

“I like things that move deeply and precisely and not too fast,” Mrs. Leff commented. “And teaching the deaf is very slow, long, drawn-out process,”

The children who are deaf will go to state or private schools for the deaf, while some of the hard of hearing children will be able to enter public schools where their speech will be helped further by speech therapists.

It is possible, she said, for some of the deaf children to attend regular high schools and colleges, and many have done this.

“I’m sure that for me getting a sound or a word from a child after meeting many obstacles is as satisfying as climbing Mt. Everest is to others,” Mrs. Leff said.

In addition to her work, she is a member of the Sisterhood of the Temple Beth Sholom and is on the board. She also assists with the Sunday school there. Among her hobbies are bridge playing, reading and cooking. Another that she finds restful is the refinishing of furniture, including her dining room buffet which she has done twice.

Deafness, according to Mrs. Leff, is the least handicapping of the handicaps since a deaf person who has been taught to speak and lip read properly can lead a fairly normal life, receive an education, marry, raise children and hold down jobs where speech isn’t vital.

Most of the deaf children today were born that way, with the number who became deaf later in childhood going down in recent years, since the diseases which caused deafness in the past either have been almost eliminated or reduced in severity by wonder drugs. Signs that a child may be deaf usually appear while he is still an infant, according to Mrs. Leff. A child who doesn’t startle or look around at a sudden, loud noise, one who doesn’t look to find the source of a familiar voice, a two-year-old who isn’t talking or an older child who doesn’t seem to pay any attention to what people say to him may be deaf or hard of hearing and should be examined. Although a child under four is too young for classes, children of two should be instructed by their parents.

“The younger you start working with a child, the easier it is on the child,” Mrs. Leff said. Parents of very young deaf children, she said, can receive help from the John Tracy Clinic in Los Angeles which will send them a free home study kit. The parents of deaf children should teach the children to look at them when the parents are speaking. And the children should be made to talk by not giving them what they want until they have asked for it. Even when the children are being taught in school, the parents are vital to their progress, since if they aren’t made to feel that speech and language is needed, it will become just another school subject.

Mrs. Leff said that as far as she knows, she is the only teacher of the deaf in Topeka. Though she says it is a proven fact that Kansas has a higher incidence of deafness than any other state in the union, it has few facilities for them. The expense of setting up special facilities and the need for specially trained teachers generally is what is keeping the number of schools to a minimum, especially in rural areas, though many larger cities in recent years have set up special schools. Mrs. Leff pointed out that it is only recently that people have begun to realize that deaf children shouldn’t be classified with criminals or put into homes for the feeble-minded simply because they can’t talk.

Teaching the deaf, as Mrs. Leff does in Topeka, is a very modern idea indeed and has only recently come into widespread use.